Variable Scales: The Secret to Dynamic Jazz Piano Improvisation

Every jazz pianist has been there: you’re soloing over a static chord, armed with the “right” scale, but your improvisation feels flat and uninspired. Despite playing all the “correct” notes, something vital is missing.

Watch the video demonstration above to hear these concepts in action, or continue reading for the full explanation. Musical notation for all scales discussed is provided below the article.

The Limitations of Traditional Chord-Scale Theory

One of the first questions we ask as jazz piano students is: “Which scales should I use to improvise?”

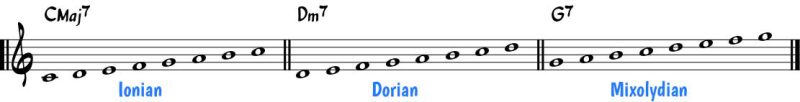

The standard answer they receive is the traditional chord-scale relationship approach—the idea that each chord has a corresponding scale: The Ionian for Cmaj7, the Dorian for Dm7, the Mixolydian for G7.

This approach makes theoretical sense, but it often leads to solos that sound mechanical and lifeless. Why? Because it focuses on vertical harmony (which notes fit the chord) rather than horizontal motion (how to create harmonic movement).

The result: your melody moves, but your harmony stands still, and your solo sounds static.

The Problem with Static Improvisation

Even when playing over a chord progression, applying a single scale to each chord creates a solo that sounds like disconnected fragments. This problem becomes even more apparent when playing over static vamps, where a single chord, such as Dm7 or G7, lasts for several measures.

Instead of creating musical motion, you end up circling the same seven notes, leading to repetitive phrases that lack direction. Your solo becomes a prisoner of the chord, rather than a story that moves through it.

But that’s not what the masters do.

What Professional Jazz Pianists Do Differently

Listen to players like Bill Evans, Herbie Hancock, or Chick Corea soloing over a single chord, and you’ll notice something remarkable: their lines create a sense of harmonic movement, even when the underlying chord remains static.

Their secret? They don’t just play scales—they imply harmonic progressions within their melodies.

Even over a single chord, professional improvisers suggest movement by referencing familiar jazz progressions like II-V-I within their phrases. Rather than being confined by the chord, they use it as a canvas for melodic storytelling.

Introducing Variable Scales: The Bridge to Dynamic Improvisation

To bring this approach into your playing, I’ve developed what I call **Variable Scales**—a concept that introduces harmonic motion into your soloing, especially over static chords.

What is a Variable Scale?

A Variable Scale is a scale that ascends in one form and descends in another, creating built-in harmonic movement.

This problem-solving approach has deep historical roots. Consider the Classical Melodic Minor Scale, which ascends with raised 6th and 7th degrees, and descends as natural minor (with lowered 6th and 7th).

This scale wasn’t created arbitrarily, it was specifically designed to solve a voice-leading problem. The raised 6th and 7th degrees in the ascending form create a smoother melodic line with a stronger pull toward the tonic, while the natural minor descending form avoids awkward augmented intervals and maintains smooth voice leading back to the tonic.

In the same way, we can apply this problem-solving approach to jazz improvisation. Just as classical composers developed variable forms to address voice-leading issues, we can create variable scales that solve the problem of static harmony in jazz improvisation.

By using Bebop Scales as our foundation and applying the variable concept, we create a tool that specifically addresses the challenge of generating harmonic motion over static chords, one of the most common obstacles jazz pianists face when improvising.

Variable Scale Example 1: The Minor Variable Scale

Let’s say you’re improvising over a Dm7 chord that lasts for four measures. The typical approach would be to use D Dorian.

However, there’s an inherent rhythmic problem with this and other traditional seven-note scales: when played across multiple octaves in 4/4 time, the harmonic alignment gets disrupted. The tonal centers—those chord tones (D-F-A-C for Dm7) that should carry melodic weight—often end up falling on weak beats, while non-chord tones land on strong beats. This creates unintentional accent patterns that work against the natural swing rhythm.

This is where bebop language offers us a brilliant solution. Jazz pioneers like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie instinctively solved this problem by adding chromatic passing tones to the standard scales, creating eight-note structures now known as Bebop Scales. These carefully placed eighth notes restore the harmonic balance by ensuring that the tonal centers (chord tones) consistently fall on strong beats, particularly downbeats. This rhythmic-harmonic alignment is fundamental to authentic jazz phrasing—it’s what gives bebop lines their characteristic “swing” even when played as straight eighth notes.

For our Dm7 chord, the Bebop Minor Scale provides this rhythmic-harmonic advantage.

But in the bebop language, we can take this concept even further.

Instead of treating Dm7 as an isolated entity, consider it as part of a II-V movement (Dm7-G7). This allows us to create a Variable Scale that ascends as the D Minor Bebop Scale and descends as the G Bebop Dominant Scale.

This is what I call the “Bebop Minor Variable Scale”, and here’s what makes it particularly powerful: it works perfectly over both chords in the II-V progression. You can apply this same variable scale whether you’re soloing over a static Dm7 (the II chord) for several measures or over a static G7 (the V chord).

When played over Dm7, it creates an implied harmonic motion by suggesting movement to G7, even though the actual chord hasn’t changed. When played over G7, it references both the current dominant chord and its preceding minor chord, adding harmonic depth to your lines. This dual functionality makes it an incredibly versatile tool for creating melodic lines that tell a harmonic story.

Watch the video demonstration to see this Bebop Minor Variable Scale played over both Dm7 and G7 static vamps, with complete musical notation provided below the article.

Variable Scale Example 2: The Blues Variable Scale

The Blues present another perfect opportunity for variable scales. Over the Blues, the two most common options pianists use are the Major Pentatonic Scale, which emphasizes the major 3rd, which emphasizes the minor 3rd, and the Minor Blues Scale. Over the C7 Blues, these would be:

Rather than choosing one or switching between them, we can combine them into a Blues Variable Scale, which ascends as the Major Pentatonic with passing b3, and descends as the Minor Blues Scale.

This variable scale encapsulates the essential blues tension between major and minor tonalities in a single melodic structure. It works beautifully over the entire 12-bar blues progression.

The video demonstrates this Blues Variable Scale in action, showing how it creates authentic blues lines with built-in tension and resolution.

Why Variable Scales Work: Combining Melodic and Harmonic Motion

Variable scales solve two major problems simultaneously:

1. Rhythmic/Melodic Phrasing: The eight-note structure derived from Bebop scales creates phrases that align naturally with the 4/4 time feel.

2. Harmonic Motion: By implying progression within the line, variable scales create a sense of movement and resolution even when the harmony is static.

Instead of playing static scales over static chords, you’re now creating phrases that suggest movement, giving your solos the dynamic quality that defines authentic jazz language.

Conclusion: From Theory to Musical Expression

The ultimate goal isn’t to play scales (even variable ones) up and down, but to create musical phrases that incorporate this concept of harmonic movement.

The variable scale approach helps you transcend the limitations of traditional chord-scale relationships by combining scale theory with harmonic awareness, all within the context of authentic jazz language.

Remember: the greatest jazz musicians aren’t thinking about scales when they improvise, they’re telling stories. Variable scales are simply a tool to help you develop the vocabulary needed to tell your own musical stories with greater depth and expression.

Next time you’re soloing over a static chord or vamp, try applying the variable scale concept. You might be surprised how quickly your improvisations transform from exercises in scale-playing to genuine musical statements that move and breathe.

Your piano will thank you, and so will your listeners.

For more in-depth instruction, subscribe to the Series at insidepiano.com/portal.